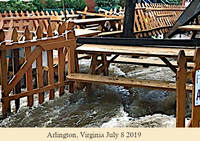

I mentioned previously that we had an impressive downpour a few weeks back here in Arlington, Virginia. Four and a half inches of rain in an hour is a lot of precipitation, and the result was flooded basements and a few washed away structures. Quick, heavy downpours have become rather more frequent here in recent years, whatever the reason.

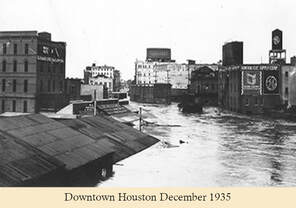

Flooding is something I grew up with in Houston, Texas. Everyone remembers Hurricane Harvey. What fewer folks are aware of is that for the last twenty years Houston has averaged five days of flooding a year, according to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information. I doubt this is some recent trend; look online and you can find this picture of downtown Houston inundated in 1935. More than fifty years back, I can remember walking out of my elementary school to find the street leading to my house under a couple feet of water, not from a hurricane or tropical storm, just the result of an afternoon thundershower. Those are common throughout the year in Houston because the place is hot and humid most of the time. You get accustomed to clouds forming slowly into big clouds and then impressive thunderheads that dump a torrential soaking around 4:00 or 5:00 in the afternoon. Doesn’t cool things off, either. Evenings after a thunderstorm are just as hot and even more humid.

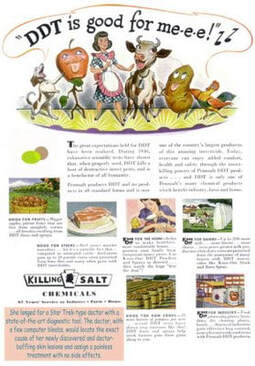

Much of this is due to simple geography. Houston was founded at the confluence of two streams, White Oak Bayou and Buffalo Bayou. This is an area of town known today as Allen’s Landing, a perpetuation of the myth that Houston’s founders, John Kirby Allen and Augustus Chapman Allen, somehow arrived there in a canoe or something, disembarked and declared the area a lovely environment to settle. The Allen brothers indeed founded Houston, but not in such a picturesque fashion. The two land speculators managed to acquire some 6,600 acres of coastal prairie in 1837. Having been provisioners to Sam Houston’s army, they decided to found a city and call it Houston. John was a member of the Republic of Texas House of Representatives and even got the city declared the capital for a short time. You can read all about the Allen brothers on Wikipedia. John died of congestive fever in 1838, by the way. A synonym for “coastal prairie” could well be “swamp,” if my experience of Houston is indicative. People who live in swampy, mosquito-infested marshes tend to get fevers a lot. By the time I was growing up there, the mosquitoes weren’t as big a problem, though: the city had these trucks driving around spraying DDT.

In fact, Houston is one of the best examples of Man vs. Nature in the world. Houstonians have been persistent since the first settlers who decided to stick out the heat, humidity, and poisonous reptiles, even after the Republic of Texas came to its senses and relocated the capital to Austin, although at the time the place was known as Waterloo. I like to imagine an alternative history where the state kept that name rather than renaming the capital for Stephen F. Austin. Anyway, those Houstonians who stayed were determined to build something. In 1841, they declared the dock that had been built at that confluence of White Oak and Buffalo Bayous the “Port of Houston,” despite being roughly fifty miles from the Gulf of Mexico. Houston wasn’t much of a port until Buffalo Bayou was widened and deepened all the way to Galveston Bay after the 1900 hurricane pretty much leveled Galveston. Now it’s one of the biggest ports on the planet. Galveston still has better beaches,though.

Houston’s growth was also enabled by the development of air conditioning. Although that elementary school I occasionally had to wade to get out of didn’t have air conditioning, increasingly every other venue did. All the movies houses, including those I discuss in an earlier post, used to advertise “air conditioned comfort.” Kids in class didn’t need comfort, I guess. Hey, there was a big fan in every room to keep the hot air circulating, so who am I to complain? And eventually even the schools succumbed to Houston’s drive to make the place habitable.

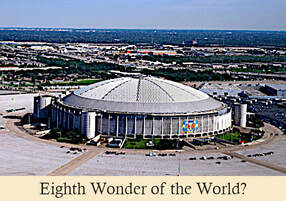

Interesting thing about air conditioning, by the way. As anyone familiar with basic physics can attest, you don’t really “cool” air; you just move heat from one place to another, like from inside your cinema or domed stadium to just outside the building walls. This means that for every space being cooled, some other place is getting warmer. Add ever growing expanses of concrete reflecting more and more heat and you can see why Houstonians spend most of their time in those air-conditioned indoors.

Perhaps nothing symbolized the determination of Houstonians to spit in the eye of Mother Nature more than the Astrodome. City fathers would not allow torrential rain and stifling heat to prevent attracting a major league baseball expansion team; rather, they built the first domed stadium and dubbed it the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” Semi-transparent lucite tiles made up the roof to allow in sunlight to nourish the grass field. Unfortunately, the grass tended to give off moisture, creating occasional indoor “rain.” And the glare through those tiles made tracking fly balls almost impossible, so eventually large swaths were painted gray. This robbed the grass of sunlight, killing it. No problem. Astroturf was invented. And, of course, the entire thing was air-conditioned. Watching a game in the Astrodome was as comfortable as seeing a movie in one of those air-conditioned cinemas. The crowds were similar, too: people sat in respectful silence while the game progressed.

Despite this impressive edifice, there was actually one rain-out during the Astrodome’s tenure. In June 1976, massive flooding made it impossible for fans to get to the game. Did I mention that Houston floods a lot?

Despite this impressive edifice, there was actually one rain-out during the Astrodome’s tenure. In June 1976, massive flooding made it impossible for fans to get to the game. Did I mention that Houston floods a lot?

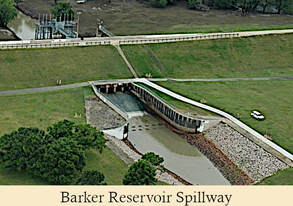

It’s not like Houstonians haven’t tried to solve the flooding issue. In the aftermath of that 1935 flood pictured above, the Army Corps of Engineers proposed and built the Addicks Dam and Addicks and Barker Reservoirs to help prevent downstream flooding of Buffalo Bayou. Sure, there were still floods in Houston, like the one that kept people away from the Astrodome that night, but apocalyptic ones inundating the entire downtown and surrounding areas were avoided. Until Harvey, that is. Nothing can prepare a city for that much rain. Controlled releases of water from Addicks Dam were required to keep the reservoirs from overflowing, and mostly that just affected the downstream flood plains. Too bad developers had built thousands of homes in parts of that flood plain, but, hey, omelettes and broken eggs, right?

From what I read, people who study climate believe storms packing more water and dropping it with greater intensity will increase in the rainy parts of the planet. This is not good news for Houston (nor for my current residence in northern Virginia, I might add). An easy answer, one you find folks throwing out there a lot on the Internet, is that cities like Houston are untenable in the long run and the country should stop investing in keeping them dry. Humans don’t really think like that, though. If your home is in Houston, you just keep trying to cope with what life and nature throw at you. Barring another Harvey, the thinking goes, all will be okay.

God willing and the creek don’t rise . . .

From what I read, people who study climate believe storms packing more water and dropping it with greater intensity will increase in the rainy parts of the planet. This is not good news for Houston (nor for my current residence in northern Virginia, I might add). An easy answer, one you find folks throwing out there a lot on the Internet, is that cities like Houston are untenable in the long run and the country should stop investing in keeping them dry. Humans don’t really think like that, though. If your home is in Houston, you just keep trying to cope with what life and nature throw at you. Barring another Harvey, the thinking goes, all will be okay.

God willing and the creek don’t rise . . .

By the way, years ago I wrote a song about often-drenched Houston. I even recorded it. I’ve attached it below for stout-hearted souls brave enough to endure my amateur musicianship and lousy voice. I’ve tried over the years to get real singers and musicians interested enough to produce a better version. Sadly, my efforts have been to no avail. So here is “Houston, The Last Wave.” If the waters don’t move you, maybe it will.

David

David

RSS Feed

RSS Feed