In recent years, I’ve become quite a fan of Kelvin Sampson, currently coach of the University of Houston men’s basketball team. He’s one of the most successful college basketball coaches in the history of the game, of course, so it’s not surprising he attracts a large fan-base. Yet I knew nothing about him before he resurrected the UH basketball program.

My relationship with basketball is local and personal. I grew up in Houston, Texas. As a kid, the only organized sports I participated in were baseball and basketball, both as a member of youth teams organized by our Southern Baptist church. Every summer we played church league baseball and in the Fall we competed in a church basketball league. I was lousy at both sports. My favorite activity growing up was reading, mostly science fiction. I managed to get through multiple baseball seasons without ever getting a hit, spending a lot of time on the bench.

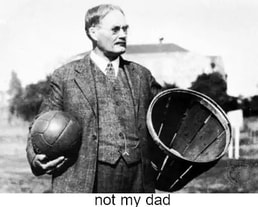

I wasn’t much better at basketball. However, my dad coached the team. I played every minute of every game. According to him, this wasn’t nepotism. He explained to me repeatedly that league rules required him to have one player from every age group on the court at all times, and freakishly I was the only kid in our church in my age group. After that explanation came the admonition that I was to avoid doing anything that might cost us a game. Don’t shoot, don’t try to dribble, just grab the ball if it was near me and give it immediately to one of the other kids. Oh, and don’t foul out. I suspect my dad was lying about that age requirement. Why he wanted me on the court every minute given his realistic view of my lack of skill remains a mystery.

Given that I was a klutz and my own father pretty much reminded me of that every basketball season, these are not glorious memories from my childhood. My most vivid one is from a game we lost. Before we’d even gotten off the court, one of my team-mates stuck his face in mine and yelled, “We lost because of you!” I was nine or ten years old at the time. I remember in days following going over the whole game repeatedly in my mind searching for just what I could have done that cost us that game. Assuredly, I hadn’t done much to win the game. I didn’t score, didn’t even attempt a shot. I’d grabbed a couple of rebounds and harassed whoever ventured into my forward slot in our 2-1-2 zone defense, without fouling, of course. I hadn’t fumbled the ball at a critical moment. Didn’t even get fouled and miss a free throw, always embarrassing because I was terrible at free throws, not being strong enough to actually shoot from that far back and simply resorting to heaving the ball in the general direction of the basket.

Of course, maybe that kid’s complaint was that I was keeping a more talented player on the bench by being constantly on the floor. In hindsight, I realize how laughable this is. We were all 9 to 11 years old and it was the early 1960s. Our team was pretty good, winning more than losing, because we had one kid who was taller than the rest of us and another kid who could dribble the ball and actually shoot it from inside ten feet. Our tall kid got a lot of rebounds and the kid who could shoot managed four or five baskets a game. This made us one of the better teams in the kids’ church league. Oh, and my dad somehow learned about the “fast break.” He told our tall kid to heave the ball down court whenever he got a defensive rebound, and a few times one of our kids would even manage a lay-up. As final scores were generally something like 17-12, we were successful more times than not.

Of course, sometimes you’d run into a team that also had a tall kid and actually had two players with skills. That’s what happened to us during the game I somehow “lost.” And, as you’ve probably figured out, our “skill” player, a kid named Joey, was the one who yelled at me. Joey knew he was our best player, and he liked to make sure we knew it, too. My only other memory of Joey is from a game we lost after he fouled out early in the third quarter. We were playing in a tournament at a YMCA. When he fouled out, he walked off to another court and got into a pick-up game. So much for cheering on your team-mates.

As I grew older, those early basketball memories faded. I didn’t leave basketball behind, though. This was Houston, after all, home to one of the nation’s most successful college basketball programs. I was thirteen years old when UH, led by Elvin Hayes, met UCLA and Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul Jabbar) in the Astrodome for the “game of the century.” I grew up following UH basketball, from being excited to watching possibly the first 6’9” point guard, Louis Dunbar, to seeing every Phi Slamma Jamma game played. Yes, I still cringe at the replay of Lorenzo Charles grabbing that Derek Wittenberg airball and dropping it through the basket along with UH’s national championship aspirations.

My wife and I moved away from Houston in 1986. Over the next twenty years, our interest in UH sports remained, but at a distinct distance. Hard as it may be to believe these days, being more than a thousand miles away meant following your “home” team was reduced to reading box scores in the newspaper and very rarely having them show up on television or at a venue near enough to go see them. Add being posted overseas a couple of times for a few years; well, the bond lapsed.

I was back from overseas and a few years from retirement when I noticed one day that my old UH cougars had made the NCAA tournament. Even more exciting, the game was televised where we lived. I watched them for the first time in ages. They suffered a heartbreaking, last-second loss, which certainly brought back memories of that NC State game. But this team was different from the UH teams I’d watched growing up. Those teams scored a lot of points and gave up points in return. This team played vicious man-to-man defense and crashed the boards. I resolved to start watching again, aided by the advent of new streaming services that made almost any sporting event viewable with the right subscription.

I also started reading about UH coach Kelvin Sampson, which has included learning about the Lumbee tribe in North Carolina. Theirs and his are histories worth researching. So I’ve become a fan. If I see a clip of him being interviewed, I stop what I’m doing and listen. I came across one the other day in which he was explaining the #Eracism shirts he and his staff were wearing. He said, “I remember segregation.” Suddenly, I did, too. I remembered the one year of church league basketball when I actually felt part of a team.

The year was 1966 or 1967. In the parlance of the day, the neighborhood around our church had started to “change.” What this meant in the segregated South was that African-Americans were beginning to buy and rent in the area and whites were leaving. What caused these shifts is a chicken and egg discussion that I won’t go into, but the driver was always the fact that white people didn’t like living next to African-Americans. It’s called racism.

Our church stayed at first. Attendance started dropping, but a core group kept trekking back to the old building for services. My dad was part of that group, mostly because he ran the boys’ youth program and also, being an accountant, did the church books. With the arrival of the next basketball season, though, things were pretty dire. Our first practice attracted exactly two of us. Not enough for a team.

I should point out that the church had gone to considerable trouble over the years to participate in the league. Long before I played, a concrete basketball court had been built in the back of the church parking lot. About the time I was old enough to participate, a few church members had donated money and labor to enclose the court in a corrugated metal building. Someone donated a time-clock, and after my first year, some enterprising men actually laid a hardwood court over the concrete. It wasn’t the Boston Garden by any means, but it was certainly one of the nicer church facilities in the Houston area at the time.

By the second practice that year, it was pretty evident we weren’t going to be able to field a team. My dad kind of forlornly tossed a ball to me and the other kid to shoot lay-ups. And then, about a dozen African-American kids opened the door and peeked inside. A couple came in and asked it they could play. My dad explained to them that the gym was for members of the church. Then, after a pause, he added, “But if any of you want to come to our youth meetings on Wednesdays, you can play in our league.” They left.

The following Wednesday, nine of them did, in fact, show up. They sat politely through our Bible reading and discussion. I suspect most of them knew the Bible better than I did. At the end of the session, my dad announced the next basketball practice on Saturday for anyone interested. One of them smiled and said, “We’ll be there, sir!”

The other white kid never came back. From that point on, my dad and I provided the diversity element. But that Saturday we had enough for a full five-on-five scrimmage. We did lay-up and passing drills and practiced playing that 2-1-2 zone, but during scrimmage we just played man-on-man. After that first practice, we continued to work on the zone, mostly so we were all familiar playing against it. In games, though, we played man. Watching just one scrimmage convinced my dad he had kids who could maintain actual defense for extended periods.

This was the best team I ever played on. I learned a lot. One thing I learned is that these kids weren’t stronger than me nor faster nor possessing of some natural talent I lacked. What they had was a willingness to practice. Despite what a lot of teams we eventually played probably thought, my team-mates didn’t walk into that gym already highly skilled ballers. My dad actually showed them a few tricks.

Take boxing out for rebounds. This is not something intuitive. When you’re ten years old, your natural reaction during a basketball game is to watch the ball. When someone shoots, you watch the ball and then move toward it to get the rebound if it doesn’t go in. It’s pretty much up for grabs. Tallest kid usually wins. Unless you box out. This means finding the kid closest to you as soon as the ball is shot and positioning yourself between him and the basket. Then you look up to find the ball. Boxing out doesn’t require any great athletic ability or even much skill. Amazingly, though, if you habituate yourself to do it, a lot of rebounds just fall right into your hands.

I don’t remember Joey ever boxing out. But all my new team-mates did once my dad explained the concept. We got most of the rebounds. We also learned not to hold the ball or try to dribble out of the pack after defensive rebounds. Find a team-mate on the wing and get him the ball. Then run to the other end of the court. We scored a lot of lay-ups and won a lot of games, every one that season, in fact.

The moment that stands out for me from that year came in the first game. We were winning handily. I actually hadn’t played too badly, getting a few rebounds and denying the ball to whoever I was guarding fairly effectively. Toward the end of the game, I heard one of my team-mates say to another, “Hey, coach’s son hasn’t scored.” The rest of the game, they all kept passing me the ball and yelling for me to shoot. I finally forced up a couple of shots. No luck, I’m afraid.

This upset my team-mates. One of them told me after the game that I needed to shoot more. I explained that I wasn’t very good at shooting and had always been told just to pass the ball.

“You won’t ever get better if you don’t shoot the ball.” For the rest of the season, it became the mission of my team-mates to improve my shooting ability and get me on the scoreboard. I think I finally scored a couple of baskets in the last few games. Whatever else, the members of that team looked out for each other. For me, that was a first.

A final note on that season of basketball. We made it to the league championship. As we were warming up, one of the officials came over to my dad and told him that our opponents’ roster had six or seven players from a neighboring junior high varsity team, a violation of league eligibility rules. He offered to disqualify them, meaning we would win by forfeit. My dad called us all over, explained the situation, and asked what we wanted to do. As you can imagine, the response was unanimous: “We want to play them!” Play them, we did. It wasn’t close. We won pulling away in the third quarter.

That team only existed for one year. Most of the church weren’t too pleased with my dad. The majority of the church elders had been lobbying to relocate to a whiter part of the city. My dad provided one of the few voices arguing we should stay put and try to attract members from the changing community. He was roundly outvoted. The church decamped to the suburbs and we stopped going. The fact that my dad had brought our team to one prayer meeting and was asked not to do that again had already left him pretty bitter. As for me, I was just happy not to have to attend church any more and have people preach to me that I was going to burn in Hell.

I didn’t play much basketball the next few years. I also lost touch with the kids from that last team. Segregation was still the norm, legally and socially. I remember running into one of my former team-mates at a junior high football game a year or so later. We were from the opposing schools but both wearing our respective band uniforms. He waved, I said hello. That was about it. Several of the members of my band asked me, “How do you know that black kid?” I suspect my former team-mate got similar questions. To this day I regret that we all just went our separate ways. For those few months, I had been closer to them than I would be to any other classmates or team-mates for the entire time I was growing up. It would be years, in fact, before I even met any other African-Americans.

That was one of the many crimes of segregation, robbing us of the chance to get to know and learn from each other.

Kelvin Sampson and other coaches have created “Eracism,” a social inclusion movement committed to bringing forth change through education, awareness, and action with current and former college basketball coaches leading the way. You can read more about it here: https://spark.adobe.com/page/bq0qbkjhkLH3q/. Check it out and give it your support.

Racism sucks.

David Manuel

December 14, 2021

My relationship with basketball is local and personal. I grew up in Houston, Texas. As a kid, the only organized sports I participated in were baseball and basketball, both as a member of youth teams organized by our Southern Baptist church. Every summer we played church league baseball and in the Fall we competed in a church basketball league. I was lousy at both sports. My favorite activity growing up was reading, mostly science fiction. I managed to get through multiple baseball seasons without ever getting a hit, spending a lot of time on the bench.

I wasn’t much better at basketball. However, my dad coached the team. I played every minute of every game. According to him, this wasn’t nepotism. He explained to me repeatedly that league rules required him to have one player from every age group on the court at all times, and freakishly I was the only kid in our church in my age group. After that explanation came the admonition that I was to avoid doing anything that might cost us a game. Don’t shoot, don’t try to dribble, just grab the ball if it was near me and give it immediately to one of the other kids. Oh, and don’t foul out. I suspect my dad was lying about that age requirement. Why he wanted me on the court every minute given his realistic view of my lack of skill remains a mystery.

Given that I was a klutz and my own father pretty much reminded me of that every basketball season, these are not glorious memories from my childhood. My most vivid one is from a game we lost. Before we’d even gotten off the court, one of my team-mates stuck his face in mine and yelled, “We lost because of you!” I was nine or ten years old at the time. I remember in days following going over the whole game repeatedly in my mind searching for just what I could have done that cost us that game. Assuredly, I hadn’t done much to win the game. I didn’t score, didn’t even attempt a shot. I’d grabbed a couple of rebounds and harassed whoever ventured into my forward slot in our 2-1-2 zone defense, without fouling, of course. I hadn’t fumbled the ball at a critical moment. Didn’t even get fouled and miss a free throw, always embarrassing because I was terrible at free throws, not being strong enough to actually shoot from that far back and simply resorting to heaving the ball in the general direction of the basket.

Of course, maybe that kid’s complaint was that I was keeping a more talented player on the bench by being constantly on the floor. In hindsight, I realize how laughable this is. We were all 9 to 11 years old and it was the early 1960s. Our team was pretty good, winning more than losing, because we had one kid who was taller than the rest of us and another kid who could dribble the ball and actually shoot it from inside ten feet. Our tall kid got a lot of rebounds and the kid who could shoot managed four or five baskets a game. This made us one of the better teams in the kids’ church league. Oh, and my dad somehow learned about the “fast break.” He told our tall kid to heave the ball down court whenever he got a defensive rebound, and a few times one of our kids would even manage a lay-up. As final scores were generally something like 17-12, we were successful more times than not.

Of course, sometimes you’d run into a team that also had a tall kid and actually had two players with skills. That’s what happened to us during the game I somehow “lost.” And, as you’ve probably figured out, our “skill” player, a kid named Joey, was the one who yelled at me. Joey knew he was our best player, and he liked to make sure we knew it, too. My only other memory of Joey is from a game we lost after he fouled out early in the third quarter. We were playing in a tournament at a YMCA. When he fouled out, he walked off to another court and got into a pick-up game. So much for cheering on your team-mates.

As I grew older, those early basketball memories faded. I didn’t leave basketball behind, though. This was Houston, after all, home to one of the nation’s most successful college basketball programs. I was thirteen years old when UH, led by Elvin Hayes, met UCLA and Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul Jabbar) in the Astrodome for the “game of the century.” I grew up following UH basketball, from being excited to watching possibly the first 6’9” point guard, Louis Dunbar, to seeing every Phi Slamma Jamma game played. Yes, I still cringe at the replay of Lorenzo Charles grabbing that Derek Wittenberg airball and dropping it through the basket along with UH’s national championship aspirations.

My wife and I moved away from Houston in 1986. Over the next twenty years, our interest in UH sports remained, but at a distinct distance. Hard as it may be to believe these days, being more than a thousand miles away meant following your “home” team was reduced to reading box scores in the newspaper and very rarely having them show up on television or at a venue near enough to go see them. Add being posted overseas a couple of times for a few years; well, the bond lapsed.

I was back from overseas and a few years from retirement when I noticed one day that my old UH cougars had made the NCAA tournament. Even more exciting, the game was televised where we lived. I watched them for the first time in ages. They suffered a heartbreaking, last-second loss, which certainly brought back memories of that NC State game. But this team was different from the UH teams I’d watched growing up. Those teams scored a lot of points and gave up points in return. This team played vicious man-to-man defense and crashed the boards. I resolved to start watching again, aided by the advent of new streaming services that made almost any sporting event viewable with the right subscription.

I also started reading about UH coach Kelvin Sampson, which has included learning about the Lumbee tribe in North Carolina. Theirs and his are histories worth researching. So I’ve become a fan. If I see a clip of him being interviewed, I stop what I’m doing and listen. I came across one the other day in which he was explaining the #Eracism shirts he and his staff were wearing. He said, “I remember segregation.” Suddenly, I did, too. I remembered the one year of church league basketball when I actually felt part of a team.

The year was 1966 or 1967. In the parlance of the day, the neighborhood around our church had started to “change.” What this meant in the segregated South was that African-Americans were beginning to buy and rent in the area and whites were leaving. What caused these shifts is a chicken and egg discussion that I won’t go into, but the driver was always the fact that white people didn’t like living next to African-Americans. It’s called racism.

Our church stayed at first. Attendance started dropping, but a core group kept trekking back to the old building for services. My dad was part of that group, mostly because he ran the boys’ youth program and also, being an accountant, did the church books. With the arrival of the next basketball season, though, things were pretty dire. Our first practice attracted exactly two of us. Not enough for a team.

I should point out that the church had gone to considerable trouble over the years to participate in the league. Long before I played, a concrete basketball court had been built in the back of the church parking lot. About the time I was old enough to participate, a few church members had donated money and labor to enclose the court in a corrugated metal building. Someone donated a time-clock, and after my first year, some enterprising men actually laid a hardwood court over the concrete. It wasn’t the Boston Garden by any means, but it was certainly one of the nicer church facilities in the Houston area at the time.

By the second practice that year, it was pretty evident we weren’t going to be able to field a team. My dad kind of forlornly tossed a ball to me and the other kid to shoot lay-ups. And then, about a dozen African-American kids opened the door and peeked inside. A couple came in and asked it they could play. My dad explained to them that the gym was for members of the church. Then, after a pause, he added, “But if any of you want to come to our youth meetings on Wednesdays, you can play in our league.” They left.

The following Wednesday, nine of them did, in fact, show up. They sat politely through our Bible reading and discussion. I suspect most of them knew the Bible better than I did. At the end of the session, my dad announced the next basketball practice on Saturday for anyone interested. One of them smiled and said, “We’ll be there, sir!”

The other white kid never came back. From that point on, my dad and I provided the diversity element. But that Saturday we had enough for a full five-on-five scrimmage. We did lay-up and passing drills and practiced playing that 2-1-2 zone, but during scrimmage we just played man-on-man. After that first practice, we continued to work on the zone, mostly so we were all familiar playing against it. In games, though, we played man. Watching just one scrimmage convinced my dad he had kids who could maintain actual defense for extended periods.

This was the best team I ever played on. I learned a lot. One thing I learned is that these kids weren’t stronger than me nor faster nor possessing of some natural talent I lacked. What they had was a willingness to practice. Despite what a lot of teams we eventually played probably thought, my team-mates didn’t walk into that gym already highly skilled ballers. My dad actually showed them a few tricks.

Take boxing out for rebounds. This is not something intuitive. When you’re ten years old, your natural reaction during a basketball game is to watch the ball. When someone shoots, you watch the ball and then move toward it to get the rebound if it doesn’t go in. It’s pretty much up for grabs. Tallest kid usually wins. Unless you box out. This means finding the kid closest to you as soon as the ball is shot and positioning yourself between him and the basket. Then you look up to find the ball. Boxing out doesn’t require any great athletic ability or even much skill. Amazingly, though, if you habituate yourself to do it, a lot of rebounds just fall right into your hands.

I don’t remember Joey ever boxing out. But all my new team-mates did once my dad explained the concept. We got most of the rebounds. We also learned not to hold the ball or try to dribble out of the pack after defensive rebounds. Find a team-mate on the wing and get him the ball. Then run to the other end of the court. We scored a lot of lay-ups and won a lot of games, every one that season, in fact.

The moment that stands out for me from that year came in the first game. We were winning handily. I actually hadn’t played too badly, getting a few rebounds and denying the ball to whoever I was guarding fairly effectively. Toward the end of the game, I heard one of my team-mates say to another, “Hey, coach’s son hasn’t scored.” The rest of the game, they all kept passing me the ball and yelling for me to shoot. I finally forced up a couple of shots. No luck, I’m afraid.

This upset my team-mates. One of them told me after the game that I needed to shoot more. I explained that I wasn’t very good at shooting and had always been told just to pass the ball.

“You won’t ever get better if you don’t shoot the ball.” For the rest of the season, it became the mission of my team-mates to improve my shooting ability and get me on the scoreboard. I think I finally scored a couple of baskets in the last few games. Whatever else, the members of that team looked out for each other. For me, that was a first.

A final note on that season of basketball. We made it to the league championship. As we were warming up, one of the officials came over to my dad and told him that our opponents’ roster had six or seven players from a neighboring junior high varsity team, a violation of league eligibility rules. He offered to disqualify them, meaning we would win by forfeit. My dad called us all over, explained the situation, and asked what we wanted to do. As you can imagine, the response was unanimous: “We want to play them!” Play them, we did. It wasn’t close. We won pulling away in the third quarter.

That team only existed for one year. Most of the church weren’t too pleased with my dad. The majority of the church elders had been lobbying to relocate to a whiter part of the city. My dad provided one of the few voices arguing we should stay put and try to attract members from the changing community. He was roundly outvoted. The church decamped to the suburbs and we stopped going. The fact that my dad had brought our team to one prayer meeting and was asked not to do that again had already left him pretty bitter. As for me, I was just happy not to have to attend church any more and have people preach to me that I was going to burn in Hell.

I didn’t play much basketball the next few years. I also lost touch with the kids from that last team. Segregation was still the norm, legally and socially. I remember running into one of my former team-mates at a junior high football game a year or so later. We were from the opposing schools but both wearing our respective band uniforms. He waved, I said hello. That was about it. Several of the members of my band asked me, “How do you know that black kid?” I suspect my former team-mate got similar questions. To this day I regret that we all just went our separate ways. For those few months, I had been closer to them than I would be to any other classmates or team-mates for the entire time I was growing up. It would be years, in fact, before I even met any other African-Americans.

That was one of the many crimes of segregation, robbing us of the chance to get to know and learn from each other.

Kelvin Sampson and other coaches have created “Eracism,” a social inclusion movement committed to bringing forth change through education, awareness, and action with current and former college basketball coaches leading the way. You can read more about it here: https://spark.adobe.com/page/bq0qbkjhkLH3q/. Check it out and give it your support.

Racism sucks.

David Manuel

December 14, 2021

RSS Feed

RSS Feed