The Constitution’s language concerning treason is as follows: Treason against the United States, shall consist only in levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort. No Person shall be convicted of Treason unless on the Testimony of two Witnesses to the same overt Act, or on Confession in open Court.

This narrow definition does make prosecution for treason extremely difficult. In the one case that comes closest to what Trump and his collaborators attempted on January 6, 2021—that of Aaron Burr 200 years ago—the defendant was acquitted. However, the current case involving Trump is distinguishable from the Burr case.

In secret correspondence with a U.S. general who subsequently turned against him and revealed the plot, Burr outlined his design for carving a new nation with him at its helm out of what was then Western U.S. territory. To render that a prosecutable conspiracy required an affirmative act. While a rag-tag army was being raised on an island in the Ohio River, Burr was not present and there was no evidence that he actually called for the marshaling of a military force to execute his plan. Consequently, the court acquitted him, finding that he did not levy war against the U.S.

Trump’s conspiracy, on the other hand, went much farther and was far more overt than Burr’s. In addition to plotting with Steve Bannon, Alex Jones, Mark Meadows, Bernard Kerik, John Eastman, Jeffrey Clark, Rudy Giuliani and others, Trump on January 6 appeared in front of his “army” and directed them to march on the Capitol. In his harangue to his “troops,” he employed incendiary language that they reasonably interpreted as a call to arms and action against the sitting U.S. government. Unlike the Burr conspiracy, which never got off the ground, Trump’s did levy war against the U.S.

There is even more ammunition at the Justice Department’s disposal than the distinguishing characteristics of the Trump conspiracy. In Ex parte Bollman and Swartwout, a habeus corpus case involving two Burr associates, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall interpreted the Constitution’s Treason Clause: To be a traitor, Marshall said, an individual did not have to appear “in arms against his country. On the contrary, if war be actually levied, that is, if a body of men be actually assembled for the purpose of effecting by force, a treasonable purpose, all those who perform any part, however minute or however remote from the scene of action, and who are actually leagued in the general conspiracy, are to be considered as traitors.”

This interpretation fits Trump and his insurrectionist army to a T. This raises the question posited at the beginning of this essay: why haven’t Trump and his co-conspirators been indicted for this most monstrous of crimes?

There is a reason we have a Department of Justice and an Attorney General. DOJ’s own mission statement reads: “To enforce the law and defend the interests of the United States according to the law; to ensure public safety against threats foreign and domestic; to provide federal leadership in preventing and controlling crime; to seek just punishment for those guilty of unlawful behavior; and to ensure fair and impartial administration of justice for all Americans.”

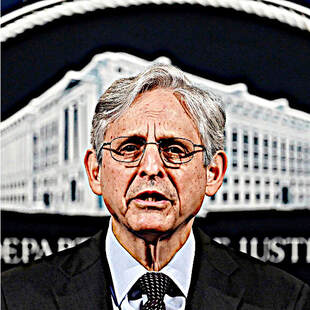

That’s pretty unambiguous. To date, DOJ and Attorney General Garland have fallen down on the job. It is a sad commentary that the Attorney General of the United States hesitates to go after the worst criminal act in our long history, possibly because he fears being branded “political.”

If Garland and DOJ are vacillating because they fear that they could lose this case, the next question to them should be: “Why haven’t you gone after Trump for the more than ten instances cited by the Mueller Report in which he obstructed justice, but could not be indicted because of DOJ’s guidelines against indicting a sitting president?” Trump is now a private citizen.

There comes a time when all good men must come to the aid of their country. That time, Mr. Garland, is now.

Dick Hermann

December 12, 2021

RSS Feed

RSS Feed