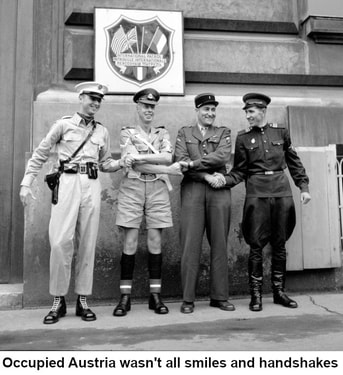

Consider Austria. At the end of World War II, Austria, like Germany was divided into four occupation zones: American, British, French and Soviet. Similarly, Vienna was also carved up into four zones. In 1954, my Viennese-born parents went back to Vienna for the first time since they escaped from Nazi-occupied Austria 15 years before. They were upset to find that their old neighborhood was firmly within the Soviet occupation zone and, unlike the sectors under Allied control, was still riddled with rubble, the residue of wartime bombing. While the nation’s economy slowly recovered in the three zones controlled by the Western Allies, the Soviet zone lagged far behind. The Soviet occupying power impounded the entire oil production in its zone while also removing factories to the USSR and requisitioning virtually the entire railroad car stock.

The next year, to universal astonishment, the Soviets abandoned Vienna and recalled their occupation forces. The quid pro quo was that Austria would declare itself a neutral nation and not take sides in the Cold War. Austria has been a neutral ever since, although it is a member of the European Union, and a party to the Eurozone currency agreement and the Schengen Area comprising the 26 European countries that have officially abolished all passport and border controls at their mutual borders.

Its adherence to neutrality has been a boon to its prosperity. In addition to hosting the third largest repository of international organizations (after New York and Geneva), Vienna has become a center of East-West trade and business. Today, Austria is one of the world’s richest countries. Vienna has earned the designation of being designated the “most livable big city” in the world.

Thanks to the Marshall Plan and Austria’s rebuilding efforts, its astonishing economic recovery led to 20 years of average annual growth between 4.5 percent and 5 percent, among the highest in the world. American largesse and rising prosperity have oriented Austria towards the West.

A declaration of Ukrainian neutrality would cost the U.S. and its NATO allies nothing. Regardless of what happens as a result of this Putin-manufactured crisis, it is highly unlikely that Ukraine would be able to join NATO in the foreseeable future. To be accepted as a NATO member, all 28 current members have to agree, an outcome that is a big stretch. Given Article 5 of the NATO treaty, which requires all member countries to consider an attack on one member as an attack on all, it is a certainty that the NATO members on or close to Russia’s borders would veto a Ukrainian application for membership.

If precedent holds, the “Austrianization” of Ukraine could be one of the best things that ever happened to that country. As with the current crop of neutral European states—Austria, Switzerland, Ireland, Liechtenstein, Malta, Sweden and Finland—it could be the beginning of a modernization and prosperity that Ukraine has never known and closer economic ties to the West.

In the West’s frantic search for an off-ramp to temper the military confrontation that Putin has conjured, this might be just what is needed.

Note. At this writing, the Munich Security Conference has convened in order for the parties to attempt to sort out the Ukraine mess. This conjures up disturbing images of an earlier Munich meeting (1939) when the West caved to a dictator, gave him free rein to consume Czechoslovakia, and added the ugly term “appeasement” to the lexicon. One hopes for a very different result this time.

Dick Hermann

February 18, 2022

RSS Feed

RSS Feed